Prompt:

Use the following Likert Scale to assess your own feelings regarding attainment of Mastery of each individual iNACOL Standard:

0 = Not at All

1 = A Little

2 = An Average Amount

3 = More than Average

4 = Masterful

Look over your list and blog about your highest scoring standard and your lowest (if you have a tie with another standard, select only 1 to write about)

Post your thoughts on why you scored as high/low on these standards as you did. In particular, what is is about your lowest scoring standard that is needing more work/focus to attain mastery? What might you do moving forward to become more expertly proficient with that particular standard (the skills and understanding it represents)?

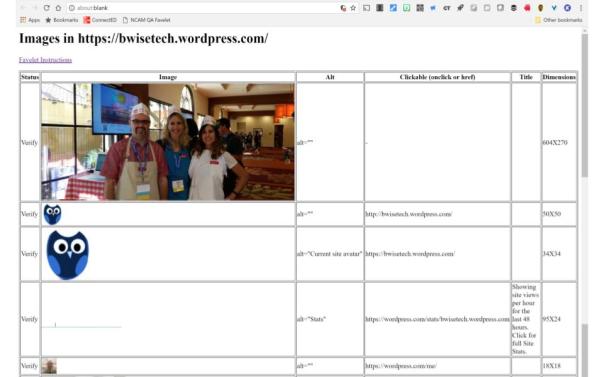

| iNACOL Standard | My Self-Rating |

| A | 4 |

| B | 4 |

| C | 3 |

| D | 5 |

| E | 5 |

| F | 2 |

| G | 4 |

| H | 4 |

| I | 2 |

| J | 3 |

| K | 5 |

I gave my highest rating to the very last iNACOL Standard K, because I feel that I am an expert in arranging electronic media resources to support student learning (International Association for K-12 Online Learning, 2011). I conduct a lot of technology trainings for teachers in my district each week, and I have consistently received my most positive feedback for my training sessions that relate to media tools like YouTube, EDpuzzle, and online multimedia game apps like Kahoot and Quizizz. Even the other Education Technology Specialists with whom I work frequently send media-related questions to me.

On the other hand, the topic that I feel I have the most to learn about is how to make online learning more accessible to all learners, including those with special needs, which is represented by iNACOL Standard I (International Association for K-12 Online Learning, 2011). Even after several Brandman courses and many meetings and trainings with my district’s special education staff, I feel there is still much for me to learn about accessibility apps, devices, and teaching methods that help ensure equitable access for students with special needs. I am not alone in this deficit. I recently spend three full days at an intensive training on my school district’s newly adopted online English Language Arts curriculum. The training session was designed and executed by a visiting representative from the textbook publisher, and most of the agenda focused on teaching methods and how to use both the electronic and print resources that the teachers will begin using next year. Almost no time was spent discussing special-education students, until I interrupted the presentation a few times to make my own observations about ways in which teachers could cut and paste the resources into text-to-speech apps.

A major textbook company developing online versions of their big-ticket programs should not treat accessibility as an afterthought, and teachers should not have to jury-rig their own accessibility solutions for their students. Little things like subtitles on videos and push button access to screen readers should are not actually little things. For some of our learners, these options can make the difference between success and failure to learn. I’m sure I can do more to support teachers with this part of their job, and I look forward to attending more conference sessions and doing more research over the next several months to further develop my expertise in working with students with special needs.

References

International Association for K-12 Online Learning. (2011). National standards for quality online teaching. Retrieved from http://www.inacol.org/resource/inacol-national-standards-for-quality-online-teaching-v2/